In 1971,

Charles Manson was found guilty of the Tate-LaBianca murders;

Joe Frazier defeated Muhammad Ali in The Fight of the Century;

The Ed Sullivan Show aired its final episode;

Starbucks and FedEx were founded;

The New York Times published The Pentagon Papers;

Richard Nixon declared the War on Drugs;

Walt Disney World opened;

The United Nations expelled Taiwan and admitted The People’s Republic of China;

DB Cooper hijacked a plane and disappeared;

Ray Tomlinson sent the first email;

Taye Diggs, Renee Elise Goldsberry, Jeremy Renner, Mary J. Blige, Regina King, Kid Rock, Lil Jon, Shawn Wayans, Michael C. Hall, Rob Corddry, Damian Lewis, Tommy Dreamer, Alex Borstein, Denise Richards, Sean Astin, Erykah Badu, Method Man, Charlie Brooker, Val Venis, Peter Sarsgaard, Jon Hamm, Johnny Knoxville, Alan Tudyk, Keegan-Michael Key, Nathan Fillion, Pavel Bure, Ewan McGregor, Picabo Street, Shannen Doherty, Selena, David Tenant, Bridget Moynahan, Sofia Coppola, Tony Stewart, Matt Stone, Paul Bettany, Lisa Lopes, Marco Rubio, Idina Menzel, Noah Wyle, Mark Wahlberg, Mark Henry, Tupac Shakur, Josh Lucas, Kurt Warner, Angela Kinsey, Elon Musk, Aileen Quinn, Missy Elliot, Julian Assange, Benedict Wong, Scott Grimes, Kristi Yamaguchi, Jim Rash, Corey Feldman, Penny Hardaway, Sandra Oh, Alison Krauss, Tom Green, Jeff Gordon, Yvette Nicole Brown, Michael Ian Black, Pete Sampras, Jorge Posada, Richard Armitage, Chris Tucker, David Arquette, Martin Freeman, Stella McCartney, Henry Thomas, Josh Charles, Amy Poehler, Lance Armstrong, Jada Pinkett Smith, Alfonso Ribeiro, Luke Wilson, Jenna Elfman, Sacha Baron Cohen, Snoop Dogg, Pedro Martinez, Craig Robinson, Anthony Rapp, Winona Ryder, Joel McHale, Christina Applegate, Ryan White, Corey Haim, Ricky Martin, Dido, Justin Trudeau, and Jared Leto were born;

While Coco Chanel, Harold Lloyd, Thomas E. Dewey, Papa Doc, Odgen Nash, Audie Murphy, Reinhold Niebuhr, Louis Armstrong, Ub Iwerks, Van Heflin, Diane Arbus, Paul Lukas, Nikita Khrushchev, Hugo Black, Duane Allman, Gladys Cooper, Bobby Jones, and Roy O. Disney died.

The following is a list of my ten favorite films released in 1971:

10) The Hospital

Dr. Herbert Brock (George C. Scott) desperately tries to keep his beloved hospital and personal life from falling apart.

When he falls in love with Barbara Drummond (Diana Rigg), the daughter of a patient at the hospital, he thinks his life has turned a corner, only to discover her father is responsible for a series of mysterious deaths at the hospital.

Fifty years later, Paddy Chayefsky’s satire still bites. Red tape and cold hearted business decisions continue to play at outsized role in determining the healthcare decisions of too many.

George C. Scott was perfectly suited for dark satire, and this faintly echoes his turn in Dr. Strangelove.

Diana Rigg was a gorgeous, talented performer who shines here and I always welcome an appearance by wonderful character actor Richard Dysart.

The movie take a turn towards self-righteousness at the end, with Brock sacrificing his happiness out of a profound moral obligation. It works, but cheapens the punch and feels a too Hollywood. If the film had been more willing to follow the dark impulses of its narrative thread, it would have been a better movie. Either Chayefsky learned this lesson, or the studio learned to trust him in time for Network.

In the early twentieth century, poor Ukrainian Jewish milkman Tevye (Topol) fights to maintain his way of life, motivated by a profound obligation to ensure his ancestors are preserved through the traditions handed down to him.

As his three eldest daughters come of age and want to marry on their own terms, he’s forced to make compromises with his identity and his value system.

In addition to this existential threat, Russian anti-Semitism forces his family to abandon the only home they’ve ever known.

At the end of the film, Tevye’s future is uncertain, but he is committed to transplanting his traditions (albeit in a modified form) to his new situation. Although he may not understand it, he is more actively engaged with his ancestors than he realizes. Tradition is not an immovable law to blindly follow for all of eternity. Rather, it’s a value system shaped and modified by generations, creating a tapestry which covers and shields us like a quilt.

Norman Jewison is an overlooked director whose understated films were deeply invested in the ways we define ourselves.

I know some wished for Zero Mostel to recreate his legendary Broadway role, but Topol is a more than adequate replacement and brings a lived in sincerity to Tevye. With Mostel, the film might have been overwhelmed by his magnetic personality.

The music is top notch and infectious.

Fifty years after is premiere, and well over a hundred after the events it dramatizes, this film reminds us compromise can be a tool for preservation. Is it better to preserve half a tradition or lose all of it?

I’d like to think the eponymous fiddler followed Tevye and his family to New York and I assume he’s still playing there.

Alex DeLarge (Malcolm McDowell) leads a gang of evil, violent criminals. One night, they cripple author F. Alexander and rape his wife while DeLarge sings “Singin’ in the Rain.” After Alex’s degenerate friends set him up to take the fall for one of their crimes, he’s arrested and imprisoned. During his incarceration, he’s subjected to the Ludovico technique, an extreme form of aversion therapy designed to make him physically ill whenever he thinks of violence.

“Cured” of his violent tendencies, Alex is released. His former gang, now police officers, take advantage of his new weakness and savagely beat him. He survives their attack and seeks refuge in the nearby home of F. Alexander who, after recognizing his whistling, tortures him until he attempts suicide.

Alex awakes at the hospital where embarrassed government ministers apologize for their mistreatment of him. Unbeknownst to them, his experience reversed the effects of the aversion therapy, and he’s once again capable of violence.

The X-rated violence and graphic sex strip away any sympathy we have for Alex, but the cruelty of his treatment is difficult to ignore. This film adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s novel asks us if it’s okay to cure him of his undesirable impulses if it means removing his humanity.

This long epic about the final days of the end of Russia’s monarchy serves as a pseudo-companion piece to Doctor Zhivago. Zhivago focuses on the impact of the revolution on those residing outside the power structure, while this focuses on the inner circle.

Tom Baker (the fourth Doctor) is wonderful as the legendary monk Rasputin. The sprawling cast includes Laurence Olivier, Jack Hawkins, Michael Redgrave, Ian Holm, Alexander Knox, Julian Glover, and Brian Cox (as Trotsky!).

Critics have often said it was too ambitious. I can’t entirely disagree. Fifty years later, it would be a prestige miniseries with time for its story to breathe and its characters to be more fully realized.

I like it because of a personal affinity for the era, the abrupt transition of Russia from sprawling, agrarian aristocracy into a supposed socialist paradise.

The demise of the Romanovs is one of the most fascinating stories of recent history. This movie, made at the height of the Cold War is clearly sympathetic (although not blindly) to the Romanov cause and serves as an exercise in the popular culture battles playing out in the shadow of geopolitical conflict.

If you find Russian history interesting, you’ll enjoy this. If you don’t, it may not be for you.

6) Bananas

While trying to impress a girl, Fielding Mellish (Woody Allen), is installed as the revolutionary new president of San Marcos, but, while visiting the US to seek financial aid for his cash-strapped country, he’s arrested and exposed as a fraud. His resulting trial is one of the most hysterical courtroom scenes in cinema, which Mellish himself calls a “travesty of a mockery of a sham.”

Allen’s early style was a clear homage to the work of his heroes, The Marx Brothers. In lieu of plot, there’s a string of loose associations from one set piece to another, like SNL with a through line. Allen’s onscreen persona in these films is the late twentieth century version of Groucho, wisecracking and adlibbing, but riddled with self-doubt. Groucho was always in command of the room, Allen is always at the room’s mercy.

This crazy film features a black woman as J. Edgar Hoover, and Allen’s first wife Louise Lasser as his love interest (they were divorced before filming began). Howard Cossell cameos as himself. Charlotte Rae is Mellish’s mother. Sylvester Stallone pops by for a blink and you’ll miss it cameo.

There aren’t enough movies made in this kinetic style anymore. Unlike his neurotic characters, Allen is fearless. He does not play it safe, but throws it all at the wall. The result is not as great a movie as those produced in Allen’s gestating fertile period, but it remains one of the funniest things he ever did.

In 1951, as Sonny Crawford (Timothy Bottoms) and Duane Jackson (Jeff Bridges) come of age in the disappearing small town of Anarene, Texas, their mentor / surrogate father Sam the Lion (Ben Johnson) towers over their lives.

While Duane pursues manipulative Jacy Farrow (Cybill Shepherd), Sonny embarks on an affair with lonely housewife Ruth Popper (Cloris Leachman).

Larry McMurtry is a magnificent chronicler of the intersection of the old and new west with an incredible ability to draw implicit connections between the colorful characters of contemporary Texas and the mythical outlaw world of the Wild West.

Sam the Lion is a direct descendant of Thomas Dunson, Rooster Cogburn, and Gus McCrae.

In the early 1970s, Peter Bogdanovich had as successful a run as any director. This, What’s Up Doc? and Paper Moon are a powerful resume. His career since has not been as impactful, but this triumvirate ensures his relevance.

Full of memorable, quirky characters, this sprawling film is bitingly funny, but also incredibly sad. None of the inhabitants of Anarene has anything resembling happiness in their life. They are all pining for something just out of reach, trapped by a nostalgia for something which likely never existed.

Claude Roc (Jean-Pierre Léaud) visits an old family friend, Anne Brown, in Wales. Encouraged by Anne, Claude romances her introverted sister Muriel. He proposes marriage, but their mother insists the couple spend a year apart first. During this sabbatical, Claude moves to Paris and has numerous affairs. He writes to Muriel breaking off their engagement and then sleeps with Anne while she’s in Paris. Anne concurrently sees the publisher Diurka.

When Muriel sends him her diary documenting her despair and sexual frustration, Claude publishes it. Muriel arrives in Paris to confront him and they briefly rekindle their affection until Claude reveals his encounter with Anne. Despondent, Muriel returns to Wales. Anne (now engaged to a Frenchman) joins her, falls ill, and dies suddenly.

When Claude learns Muriel is going to Belgium, he meets her and they finally consummate their relationship. He proposes again, but she roundly rejects him.

Claude writes a novel based on his experiences with the two sisters and Diurka publishes it.

The plot is a sordid, soap opera, with twists, betrayal and copious sex, but Truffaut never focuses on these titillating details. Instead he showcases the longing, the existential angst, and the floundering attempts to find external sources of definition in our lives.

It’s ultimately an ode to melancholia. No one is happy, but some manage their unhappiness better than others.

Jean-Pierre Léaud is not as well known in the US as he should be. He’s a lion of French cinema who started his career as a child as Truffaut’s on-screen alter ego. His steady performance is central to this film’s atmosphere. His eyes hint at a deep internal pain which he never reveals, but doesn’t try to hide.

Harold (Bud Cort) is so disenchanted with his mother he develops an obsession with death: he drives a hearse, stages elaborate fake suicides, and develops a hobby of going to funerals.

At a random funeral, he meets seventy nine year old Maude (Ruth Gordon) and the two develop a deep friendship which turns romantic. A Holocaust survivor, Maude is determined to live life on her terms. She brings Harold out of his shell and he intends to marry her. Sadly, Maude follows through with her long gestating plan to commit suicide on her eightieth birthday.

Harold is initially despondent, but ultimately learns to accept it, taking Maude’s lessons to heart.

Gordon is electric. A legendary writer when women were not frequently allowed access to creative decision making, her career is a minor miracle.

I’m a huge Cat Stevens fan and he’s in peak form, including the songs “Don’t Be Shy” and “If you Want to Sing Out, Sing Out.”

The dark gallows humor in Hal Ashby’s film make the cringe humor of Curb Your Enthusiasm seem congenial. The tone is pitch black, and I don’t love the film’s romancing of suicide, but its message of embracing life as an adventure not a challenge is inspiring. Ultimately, the film’s generous heart swallows its ample cynicism.

2) The Devils

In 17th century France, a repressed nun, Sister Jeanne des Anges (Vanessa Redgrave), falsely claims the well regarded, but philandering priest, Urbain Grandier (Oliver Reed), experimented with witchcraft and sexually molested her.

As a pretext to quell a potential Protestant revolt, authorities use these claims to justify various nefarious actions, eventually resulting in burning the innocent Grandier at the stake.

Ken Russell’s brutal film is difficult to watch, but foreshadows a lot of the contemporary criticism of religion as a bastion of harmful repressive sexual attitudes. Unlike many of its successors, this is not done with malice, but with care for the church. Russell converted to Catholicism in the 1950s and has a clear affinity for his adoptive religion. He explores her failings, hoping (I think) to use his films as a mirror, giving Catholicism the moral authority to lead the world.

I found the film to be incredibly moving, showing how corruptible and fallible men are in the face of temptation and real world consequences of pettiness. The film demonstrates how quickly rumor becomes fact and how easily people can be led to act on the flimsiest of evidence.

Oliver Reed is great as Grandier, showing the confusion and desperation of man who finds himself the subject of an absurd witch hunt. Vanessa Redgrave is wonderful as the confused nun; I may not always like her politics, but she’s a supremely talented actress.

The fervor of the Loudon witch-hunt was soon exported to Salem (which has eclipsed its predecessor in notoriety), but both were the product of a mass hysteria unwittingly unleashed in an attempt to gain power and control.

I think the church should embrace the ugly realities of life regardless of any associated controversy. I don’t think it helps to pretend faith and the faithful operate in a pristine, antiseptic environment. Films like this provide unflinching looks at the church and faithful living out Paul’s exhortation to be “in the world, but not of the world.” Sign me up for more of this.

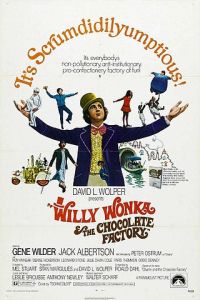

1) Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory

Famed chocolatier Willy Wonka (Gene Wilder) announces he has surreptitiously placed five golden tickets in his Wonka Bars and the recipients of these tickets will be allowed an exclusive tour of his mysterious factory.

After weeks of speculation, the winners are announced: Augustus Gloop, Violet Beuregard, Mike Teevee, Veruca Salt, and Charlie Bucket, an assuming boy who lives a quiet life with his widowed mother and four bedridden grandparents.

Wonka’s chief rival, Mr. Slugworth, promises each of the winners a healthy reward if they bring back a sample of Wonka’s latest invention, the Everlasting Gobstopper.

Upon entering the factory, the children discover it’s run by orange-colored Oompa-Loompas, who supply Wonka with cheap labor.

During the tour, the children fail to follow Mr. Wonka’s clear instructions and each meets a disastrous fate. Augustus is sucked into a pipe, Mike is shrunk, Vercua falls down a garbage chute, and Violet inflates into a giant blueberry. Only Charlie remains unharmed at the end of the tour.

Wonka reprimands Charlie for stealing some Fizzy Lifting Drinks, but after a chastened Charlie returns the Everlasting Gobstopper, a delighted Wonka informs him the entire enterprise was a test to find a successor. By refusing to align with Slugworth, Charlie passed and will inherit the factory.

Despite Roald Dahl’s disappointment with this adaptation of his book, it’s a fantastic approximation of his worldview and aesthetic, dangerous and scary but encapsulated in childhood wonder.

Thinking about the Golden Ticket, Charlie and Grandpa Joe floating to the ceiling, Violet, Veruca, and the Oompa Loompas brings a smile to my face.

An icon of a Generation X childhood, parts of the film feel dated, but it’s vastly superior to the unfortunate remake.